Architeuthis dux

Giant squid (Architeuthis dux) are the longest known cephalopods, the longest non-colonial invertebrate, and one of the largest invertebrates ever known to exist in the oceans. The largest specimens have been reported to attain mantle lengths of >3m and total lengths of >13m, but animals of this size are rarely encountered. Most records are in the 6-12m total length range. Architeuthis has small, ovoid fins, very long arms, exceptionally long tentacles, and distinctive tentacular club structure. Reviews are available of giant squid morphology, biology and distribution (e.g., Roper & Boss 1982, Roper & Shea 2013), the occurrence and morphology of A. dux in southern African waters (Roeleveld & Lipinski 1991), the systematics and biology of A. dux in Newfoundland (Aldrich 1992) and New Zealand (Förch 1998), and worldwide genetic diversity (Winkelmann et al. 2013). The huge size of these animals and the relative rarity of human encounters with them have given rise to numerous myths and mysteries, both concerning their dimensions and their supposed antagonistic, violent behavior towards ships, sailors and fishermen. Some of these accounts go back to the earliest natural history volumes published in the mid-1500s. Books by Lane (1960) and Ellis (1995, 1998) chronicle many of these stories.

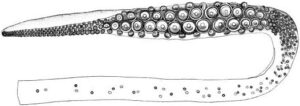

- Tentacles:with elongate, narrow clubs divided into distinct carpus, manus and dactylus regions, with suckers in four longitudinal series. Alternating pairs of suckers and knobs distributed along nearly entire length of tentacle stalk, becoming more closely-set from proximal to distal ends; carpal region with dense cluster of suckers, in 6-7 irregular series, with interspersed hemispherical fleshy knobs; manus with enlarged suckers in medial two series.

- Arms:with suckers in two series; buccal connectives attach to dorsal borders of Arms IV

- Fins: proportionally small, ovoid, without free anterior lobes; attached anteriorly to mantle rather than gladius

- Photophores: none

- Size: Mature individuals enormous, to >3m ML and >13m total length (females; males somewhat smaller)

Live animals

Giant squid were first photographed alive in their natural habitat by Kubodera et al. (2007). They have since been filmed several times in situ attracted to bait of various types including light displays mimicking the alarm display of the deep-sea jelly Atolla (the 'e-jelly', see Widder 2007 and Robinson et al., 2021 and this video clip), and dead bait such as other squid. An extended encounter was filmed from a research submersible in 2013 by NHK Enterprises Ltd (Japan), during which the animal displayed strong silvery-bronze iridescence on the mantle, head and arms. Specimens and observations on younger individuals are rare, although one can be seen in footage from shallow waters in Japan here.

Giant squid are distributed globally in tropical to sub-polar waters, usually in association with continental and island slopes. Concentrations of records are from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira; the South Atlantic in southern African waters; the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia; and circumglobally in the Southern Ocean. Specimens are rare from tropical and high polar latitudes. Since most records of Architeuthis prior to the late 20th century are from strandings, floaters and sperm whale stomachs, it is difficult to assess the vertical distribution of the architeuthids. Indirect evidence suggests a deep-sea habitat; deep net captures, as well as knowledge of sperm whale foraging behavior, now confirm that giant squid must occur across a considerable depth range, at least 300 to 1000 m. A pair of tentacles representing quite a large specimen were snagged on a fishing line at just 40 m depth off Western Australia, providing another intriguing depth data point. Captures in both bottom trawls and midwater trawls far off the bottom also suggest a broad range of habitat selection. Live photographs of giant squid have been captured at 900m off Japan (Kubodera & Mori 2005) and live video footage has been captured off Japan and in the Gulf of Mexico (Robinson et al. 2021).

Roper and Young (1972) suggested that architeuthids are most closely related to the small, deep-sea-dwelling family Neoteuthidae based on the similarities of the carpal cluster on the tentacular clubs and the absence of free anterior lobes on the fins. While the relationship does not appear to be close, it appears to be stronger than with any other family, and Fernández-Álvarez et al. (2022) placed Neoteuthidae into the superfamily Architeuthoidea. Members of this superfamily share the following characters: buccal connectives attached to the dorsal margins of ventral arms; without photophores; straight/simple funnel–mantle locking apparatus, reaching the anterior mantle margin; fins without anterior lobes, with anterior fin attachment to mantle rather than gladius; and tentacles with numerous carpal suckers (Fernández-Álvarez et al. 2022).

Many, if not most, species of Architeuthis have been described from single specimens discovered stranded on shore, floating on the surface, or taken from sperm whale stomachs. Until the 1980s, captures of specimens in fishing nets were very rare. No type specimen has been complete, and some species have been named solely on the basis of parts only, e.g., a mangled head, or a single beak. Without comparable characters, and with so badly damaged specimens, early workers had no basis for comparison among ‘species’, so they would name yet another new species of Architeuthis. Not only have many species been named, eight different architeuthid genera have been proposed:

- Architeuthis Steenstrup, 1857

- Megaloteuthis Kent, 1874

- Dinoteuthis More,1875

- Mouchezis Velain, 1877

- Megateuthis Hilgendorf,1880

- Plectoteuthis Owen, 1881

- Steenstrupia Kirk,1882

- Dubioteuthis Joubin,1899

All these genera are synonyms of Architeuthis Steenstrup, 1857. Nesis (1982/1987) and others (e.g., Jereb and Roper, 2010) considered that perhaps three valid species exist: A. dux Steenstrup, 1857, in the North Atlantic Ocean, A. martensi (Hilgendorf, 1880) in the North Pacific, and A. sanctipauli (Verlain, 1877) in the Southern Ocean. But they are not well defined nor differentiated, and not supported by recent genetic work (Winkelmann et al. 2013), which recovered a single species worldwide, A. dux, on the basis of mitochondrial sequences (which displayed remarkably low diversity). Similar low divergence has been observed in other cosmopolitan megafauna such as the basking shark (Centorhinus maximus) which has undergone an apparent genetic bottleneck due to a reduction in global population. Yet C. maximus reproduces very slowly, where A. dux may have a faster reproductive cycle and almost certainly a larger population. Winkelmann et al. (2013) proposed that that the current A. dux population may have emerged from a much smaller, uniform population and only recently expanded in distribution as their planktonic paralarvae dispersed throughout the world’s oceans. While there are no direct reports of A. dux paralarval dispersal using ocean currents, juvenile A.dux beak 13C values vary much more than those of adult specimens. This suggests that A. dux paralarvae may drift on ocean currents, with their 13C values reflecting latitudinal variation of planktonic prey 13C values. A list of all nominal genera and species in the Architeuthidae can be found here. The list includes the current status and type species of all genera, and the current status, type repository and type locality of all species and all pertinent references.

A considerable degree of morphological variation has been observed among Architeuthis dux specimens, including those collected from within a single region (see, e.g., Förch 1998).

Much remains unknown about the early life history of Architeuthis, including mating, fertilization, egg laying, embryonic development, hatching, and most of the larval development process. Are the eggs laid in huge gelatinous masses or individually? O’Shea et al. (2022) recently described five paralarvae of A. dux (ML 6.7-8.8mm) collected in epipelagic waters off New Zealand and reviewed previous published accounts of small individuals attributed to Architeuthis. Two juveniles of Architeuthis have been described from specimens of 57mm ML from off Madeira Island, eastern North Atlantic, and 45mm ML from the eastern Pacific Ocean off Chile (Roper & Young 1972). Both were taken from the stomachs of deep-sea lancetfish (Alepisaurus ferox), and exhibited marked differences in body proportions suggesting that they may in fact represent two different species. The Atlantic specimen had arms as long as the mantle, while in the Pacific form the longest arms (II-IV) were about 60% of the ML; the Pacific specimen had tentacles less than half as long as the Atlantic form. These specimens when reported were an order of magnitude smaller than the previously known smallest architeuthid. Several further small specimens have been reported as architeuthids, but close inspection reveals them to belong to other families. One specimen reported by Toll and Hess (1981) as Architeuthis is a mature male at 167 mm ML, a remarkably small size for a true architeuthid. Most cephalopods are fast-growing animals. Some species of small, shallow-water forms reach sexual maturity in 6-8 months, and most species about which growth, age and maturity data are available reach reproductive capacity within 12-18 months. Many examined Architeuthis specimens have been mature, especially the females (which are much more abundant in collections). But the age at maturity of Architeuthis is not known with certainty and published estimates have varied widely, with most falling between 2-3 and 14 years (see Perales-Raya et al. 2020 for review). Even at the rapid growth rate expected in most cephalopods, achieving a mass of 500kg or more in fewer than 3 years would be impressive. Females produce enormous quantities of whitish to cream-colored eggs, about 0.5-1.4mm long and 0.3-0.7mm wide, depending on the stage of their maturity. One female had over 5kg (over 11 pounds) of eggs in her ovary--well in excess of a million eggs. As in most oegopsids, females have a single median ovary in the posterior end of the mantle cavity; paired, convoluted oviducts along which mature eggs pass, then exit through the oviducal glands; and large nidamental glands that produce quantities of gelatinous material. Whether the eggs are laid into a large gelatinous matrix, as in most of the large oceanic squids, e.g., ommastrephids and thysanoteuthids, or are released individually, remains unknown, although the large nidamental glands suggest the former method (Roper & Boss 1982 and new information). Males tend to reach sexual maturity at a smaller size than do females. The two ventral arms, arms IV, are reported to be modified (=hectocotylized) to transfer very long, thin, cylindrical packets of sperm, the spermatangia (erupted spermatophores), to the female. As in most other cephalopods, the single, posterior testis produces sperm that move into a complex system of glands that manufacture the spermatophores. These are stored in an elongate sac, Needham’s sac, from which they are expelled during mating. The Needham’s sac of fully mature males is packed with hundreds of spermatophores, each up to 15cm long. Needham’s sac terminates in the terminal organ, which is so elongate that it extends anteriorly beyond the mantle opening, sometimes through the funnel. While mating has not been observed and the exact role of the terminal organ is uncertain, some females have been found with spermatangia, the sperm-containing sacs of the spermatophore, embedded in the tissue around the bases of the arms and the head (Norman & Lu 1997). Males have also been examined with embedded spermatangia, although these may represent self-implantation during capture.

Since the advent of commercial deep-sea trawling for orange roughy, hoki and scampi in New Zealand and Australian waters in the early 1980s, numerous Architeuthis specimens have been incidentally collected and landed for teuthologists to examine. Their total lengths have ranged from 3-4m to a maximum of 13-14m. In many cases, not only from trawls but from the other sources, the smaller specimens tend to be males. The reason for this must await further analysis and sufficient material from a single geographic region.

- Aldrich, F. A. 1992. Some aspects of the systematics and biology of squid of the genus Architeuthis based on a study of specimens from Newfoundland waters. Bulletin of Marine Science, 49(1-2), 457-481.

- Clarke, M.R. 1966. A review of the systematics and ecology of oceanic squids. Advances in Marine Biology, 4, 91-300.

- Ellis, R. 1995. Monsters of the Sea. Knopf.

- Ellis, R. 1998. The search for the giant squid. The Lyons Press, NY, 322pp.

- Förch, E. C. 1998. The marine fauna of New Zealand: Cephalopoda: Oegopsida: Architeuthidae (giant squid). NIWA Biodiversity Memoir 110. 113pp.

- Jereb, P., & Roper, C. F. 2010. Cephalopods of the world-an annotated and illustrated catalogue of cephalopod species known to date. Vol 2. Myopsid and oegopsid squids (No. 2). FAO.

- Kubodera, T., & Mori, K. 2005. First-ever observations of a live giant squid in the wild. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1581), 2583-2586.

- Lane, F. W. 1960. Kingdom of the Octopus. The Life History of Cephalopoda. Jarrolds, New York. 300pp.

- Lu, C.C. 1986. Smallest of the largest—first record of giant squid larval specimen. Australian Shell News, 53, 9.

- Nesis, K.N. 1982/1987. [In Russian]. Cephalopods of the World; Squids, Cuttlefishes, Octopuses, and Allies. T.F.H. Publications, Inc., Neptune City, NJ, USA, 351pp.

- Norman, M.D. & Lu, C.C. 1997. Sex in giant squid. Nature, 389 (6652), 683-684.

- O’Shea, S., Lu, C. C., Clarke, M. R., & Kubodera, T. 2022. Description of paralarval giant squid Architeuthis dux (Cephalopoda: Architeuthidae), with comments on ontogenetic shifts in morphology and habitat. Marine Biodiversity, 52(5), 47.

- Perales-Raya, C., Bartolomé, A., Hernández-Rodríguez, E., Carrillo, M., Martín, V., & Fraile-Nuez, E. 2020. How old are giant squids? First approach to aging Architeuthis beaks. Bulletin of Marine Science, 96(2), 357-374.

- Robinson, N. J., Johnsen, S., Brooks, A., Frey, L., Judkins, H., Vecchione, M., & Widder, E. 2021. Studying the swift, smart, and shy: Unobtrusive camera-platforms for observing large deep-sea squid. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 172, 103538.

- Roeleveld, M.C. & M.R. Lipinski, 1991. The giant squid Architeuthis in southern African waters. Journal of Zoology, 224, 431-477.

- Roper, C.F.E. & K.J. Boss. 1982. The giant squid. Scientific American, 246(4), 96-105.

- Roper, C. F., & Shea, E. K. 2013. Unanswered questions about the giant squid Architeuthis (Architeuthidae) illustrate our incomplete knowledge of coleoid cephalopods. American Malacological Bulletin, 31(1), 109-122.

- Roper, C.F.E. & R.E. Young, 1972. First records of juvenile giant squid, Architeuthis (Cephalopoda: Oegopsida). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 85(16): 205-222.

- Toll, R.B. & S.C. Hess. 1981. A small, mature male Architeuthis (Cephalopoda: Oegopsida), with remarks on maturation in the family. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 94, 753-760.

- Verrill, A. E. 1879. The cephalopods of the north-eastern coast of America. Part I. The gigantic squids (Architeuthis) and their allies; with observations on similar large species from foreign localities. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Sciences, 5, 177-257.

- Widder, E. A. 2007. Sly eye for the shy guy: Peering into the depths with new sensors. Oceanography, 20(4), 46-51.

- Winkelmann, I., Campos, P. F., Strugnell, J., Cherel, Y., Smith, P. J., Kubodera, T., ... & Gilbert, M. T. P. 2013. Mitochondrial genome diversity and population structure of the giant squid Architeuthis: genetics sheds new light on one of the most enigmatic marine species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1759), 20130273.